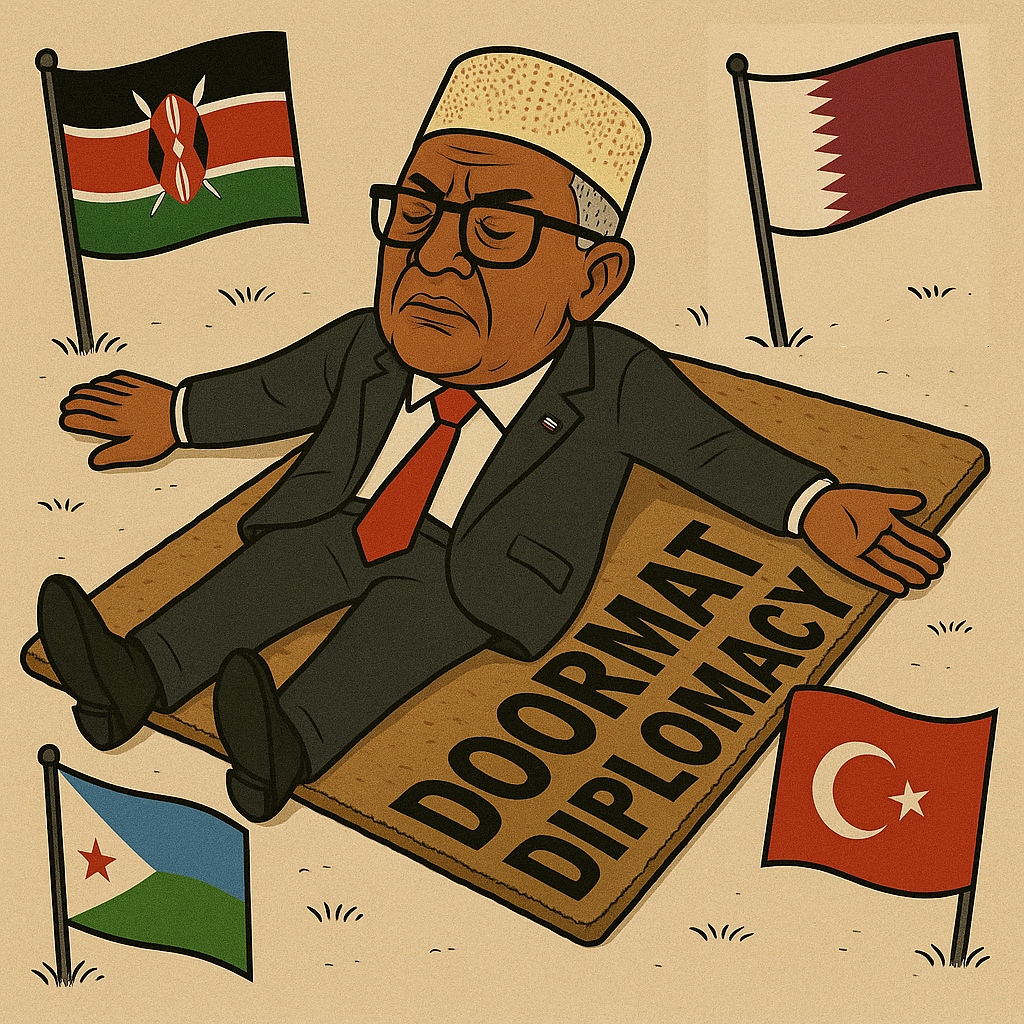

The result? Somaliland is being treated as a regional afterthought. Djibouti held parallel meetings with both Khatumo and Somaliland as if they were equals. Kenya offered Irro a protocol embarrassment. Ankara rushed to sign a joint declaration with Somalia, implicitly denying Somaliland's autonomy. All of this happened within Irro's first few months in office. The problem isn't just diplomatic inexperience - it's conceptual. Somaliland's foreign policy elite have embraced a mindset shaped by decades of NGO education, donor dependency, and liberal idealism. They act as if international legitimacy is granted through politeness and patience rather than power and principle. This is doormat diplomacy - a passive, apologetic approach rooted in the belief that if Somaliland bends low enough, it might eventually be recognised.

Roots of Doormat Diplomacy

Doormatism believes by avoiding offence and appeasing adversaries, think unrecognised countries can earn favour in international forums. It's based on constitutive theory - the idea that a state only exists if others say it does. This is fundamentally at odds with declarative theory, which defines statehood based on actual governance, population, and territory. Somaliland's new elites - steeped in NGO-driven interpretations of international law - have been conditioned to seek approval from institutions like the UN and AU, both of which have repeatedly failed Somaliland. This dependency creates intellectual paralysis. Instead of advancing bold, strategic goals, our leaders speak in empty slogans and wishful thinking.

Realism Is the Answer

Realism, the school of international relations that prioritises national interest and power over idealistic cooperation, is not just applicable to Somaliland - it is essential. Unrecognised countries do not have access to the tools of liberalism: no seat at the UN, no aid from the AU, and no backing from multilateral treaties. But realism doesn't require permission. It relies on facts on the ground. And Somaliland has facts on the ground in abundance. Since 1991, Somaliland has achieved more in terms of stability, elections, development, and peace than Somalia has in the same period - with no external help and no recognition. Federal Somalia, even with formal recognition, does not control its own territory, let alone Somaliland. In realism, this discrepancy is critical: recognition is about power, not legal theory. Realism sees the Somaliland-Somalia question not as a moral dilemma, but as a strategic choice. Much like Taiwan and China, or North and South Korea, the two entities are locked in an enduring conflict with no foreseeable resolution. The world must choose. It is no longer viable for foreign powers to have it both ways. Somaliland must force the question: What does your country gain from Somaliland - and what does it lose by siding with Somalia? Let each nation answer on the basis of its own interests. To illustrate: Kenya has fewer than 2,000 troops stationed in Somalia, a burden on its budget with marginal returns. But over 10,000 Kenyan professionals live and work in Somaliland. Which contributes more to Kenya's economy - military spending in Somalia, or remittances from its diaspora in Somaliland? The choice is obvious. Moreover, Jubaland already serves as Kenya's strategic buffer for any escalation involving Mogadishu. If economic interest, stability, and leverage are the metrics, Somaliland should be the obvious Kenyan ally. Yet no choice is made - only because no one has forced one.

Trump and the Realist Template

This is why Donald Trump's foreign policy was a gift to Somaliland. His rejection of aid-driven diplomacy, focus on bilateral partnerships, and “America First” ethos aligned perfectly with what Somaliland needs: a relationship based on shared strategic interests, not empty pledges. With Berbera's geostrategic value rising by the day, Somaliland could offer the United States and its allies access, stability, and leverage in the Horn of Africa. But to do so, we must act as a partner - not a petitioner.

Realism Is Not Immorality

Critics claim realism lacks morality. But in practice, it's often more moral than the liberalism that currently dominates. Somaliland is not asking for recognition based on sentiment. It's asking to be treated based on what it is: a functioning, peaceful, sovereign state. Denying recognition perpetuates poverty, stifles development, and invites instability. It's morally indefensible. Ironically, ignoring Somaliland in the name of "preserving unity" leads to greater fragmentation and conflict, with Las Anod being a case in point. In most state formation cases, the parent state is stronger and wealthier. In Somaliland's case, the opposite is true, and actually, Somalia isn't a parent state legally. Punishing Somaliland to reward a failed Somalia doesn't prevent secession - it just spreads suffering. What moral code justifies forcing 6 million people to suffer because 15 million are already struggling?

The Legal Argument Matters Less

While legal arguments around the Somalia-Somaliland union still hold value, realism does not depend on them. What matters is Somaliland's actual sovereignty, proven stability, and strategic importance. Even the idea of state continuity - that Somaliland simply reverted to its 1960 independence - serves only as a seal on a much broader case. It's a safeguard, not the main argument.

What's at Stake

President Bihi faced proxy wars, contested elections, and relentless pressure. Yet he never allowed Somaliland's dignity or semi-official recognition to be compromised - not even by the UN Security Council. In contrast, Irro inherited a peaceful and stable country, and yet in mere months, has undermined Somaliland's position more than any external actor ever could. This isn't just a change in leadership - it's a change in doctrine. From Bihi's assertive realism to Irro's passive Doormatism. The world is watching. The adversaries are mobilising. And Somaliland must choose: act with clarity, confidence, and realism - or fade into irrelevance, one polite handshake at a time.